Bolivia’s Lost Dinosaur Highway Reveals a Prehistoric Route Linking Peru and Argentina

- December 9, 2025

- 0

The discovery of 16,600 tracks in Toro Toro shows that Bolivia, Peru and Argentina were linked by migrating dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

A monumental discovery in central Bolivia is reshaping scientific understanding of life in South America during the final days of the Cretaceous.

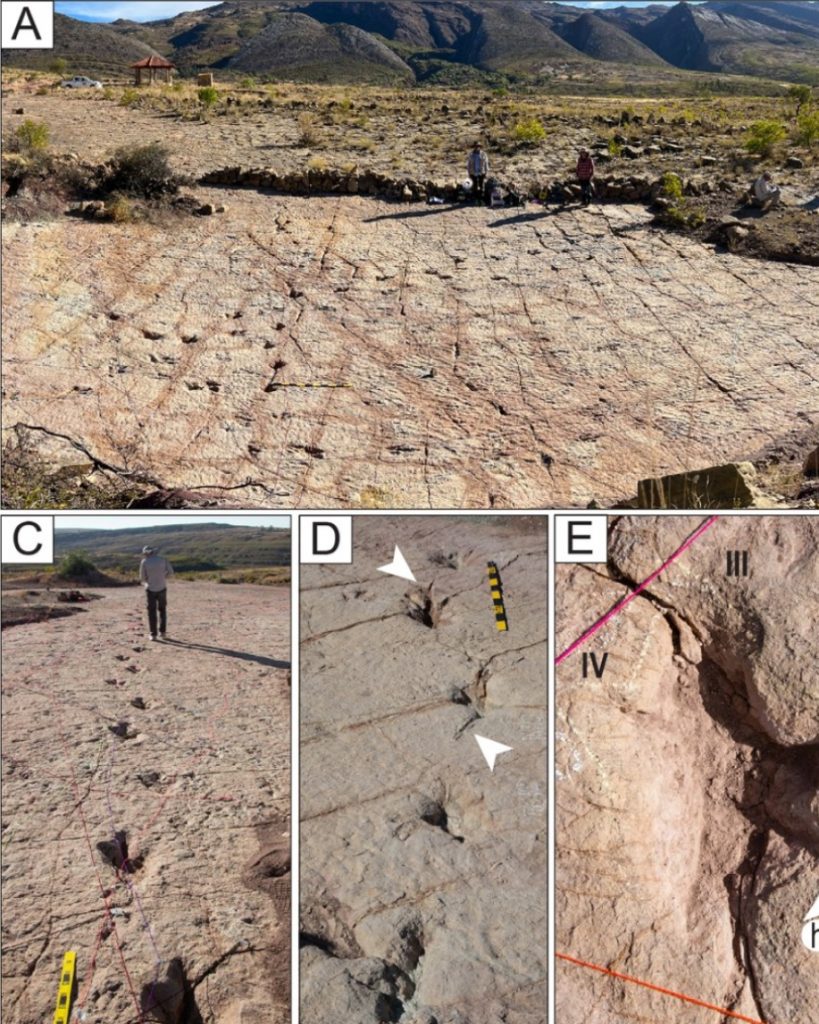

An international team of paleontologists has documented 16,600 dinosaur footprints in Toro Toro National Park—the largest collection of theropod tracks ever recorded.

The exceptional abundance and preservation of these footprints suggest the existence of an ancient natural route that once connected what is now southern Peru with northwestern Argentina, used by creatures ranging from ten-meter giants to tiny, chicken-sized theropods.

For generations, local communities crafted legends around the massive three-toed impressions scattered across the Bolivian highlands. Some believed they had been left by supernatural beasts capable of clawing through solid rock.

But scientific investigations beginning in the 1960s dispelled these myths, revealing instead that the tracks were made by bipedal dinosaurs that crossed ancient wetlands roughly 66 million years ago, when the region featured rivers, lakes, and thick sediment deposits.

The recent study, published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS One, comes after six years of systematic fieldwork by researchers from Loma Linda University, led by Spanish paleontologist Raúl Esperante.

The team meticulously documented thousands of well-preserved footprints, most of them belonging to theropods—the carnivorous lineage that includes Tyrannosaurus rex. According to coauthor Roberto Biaggi, “there is no place in the world with such an abundance of theropod tracks.”

Beyond the walking trails, the scientists identified 1,378 marks made during attempts by the dinosaurs to swim. These impressions were created when the animals clawed the soft lakebed sediment just before water levels rose, sealing their traces beneath protective layers.

For many experts, the state of preservation in Toro Toro provides a remarkably detailed window into the behavior of dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous.

Despite surviving intact for millions of years, the tracks have only recently been shielded from human activity.

Farmers once used the plateaus as threshing grounds for corn and wheat. Quarry workers blasted nearby rock formations without realizing they were destroying fossil surfaces. And only two years ago, a road construction crew nearly eliminated a major footprint site before the national park intervened. While protection measures have improved, scientists warn that the area remains vulnerable.

Strikingly, despite the vast number of tracks, skeletal remains are almost nonexistent in the region. This contrasts sharply with fossil-rich areas such as Patagonia in Argentina.

Experts propose two explanations: human disturbance likely destroyed some fossils, but more importantly, the dinosaurs may not have lived permanently in what is now Bolivia.

Instead, the uniform distribution of footprints suggests the area functioned as a natural corridor—a prehistoric highway followed by migrating animals moving seasonally from Peru toward Argentina, tracking the shifting shorelines of an ancient lake.

Footprint sizes reinforce this interpretation. Massive theropods measuring about ten meters tall traveled alongside tiny individuals only 32 centimeters high at the hip.

This diversity, captured in a single sediment layer, offers unique evidence of group movement and social dynamics. For paleontologists, it provides valuable insight into dinosaur migration patterns and ecosystem interactions just before the asteroid impact that wiped out 75 percent of life on Earth.

Researchers emphasize that footprints allow them to reconstruct details impossible to obtain from bones alone. Speed changes, sudden turns, stops, hesitations—each behavior is etched into the rock.

According to Anthony Romilio of the University of Queensland, the tracks “reveal what skeletons cannot,” offering a dynamic, moment-by-moment record of the animals’ presence.

Why did dinosaurs flock to this windswept plateau? Some scientists believe it was a freshwater lake environment that offered seasonal resources. Others suggest they may have been fleeing environmental change or seeking new territory.

What is certain is that the site is far from fully explored. Researchers suspect that thousands of additional tracks lie hidden along the outskirts of the exposed rock formations. As Biaggi notes, “this investigation will continue for years; we’re only seeing the surface of what Toro Toro has to offer.”